Asset managers: Key ESG trends in 2023

Over the last decade, attitudes towards ESG and sustainability within asset management have transformed irrevocably.

Triggered by investor and regulatory demand, fund managers are incorporating ESG into their investment processes and objectives in ever greater numbers. For example, PwC predicts that ESG-related AuM (assets under management) at investment firms will increase by 12.9% annually from $18.4 trillion in 2021 to $33.9 trillion by 2026 – totalling 21.5% of all global AuM.

The rapid growth of ESG and sustainable investing does, however, present challenges which the funds industry needs to address. Within this, boutique firms face particular risks and opportunities.

- Greenwashing

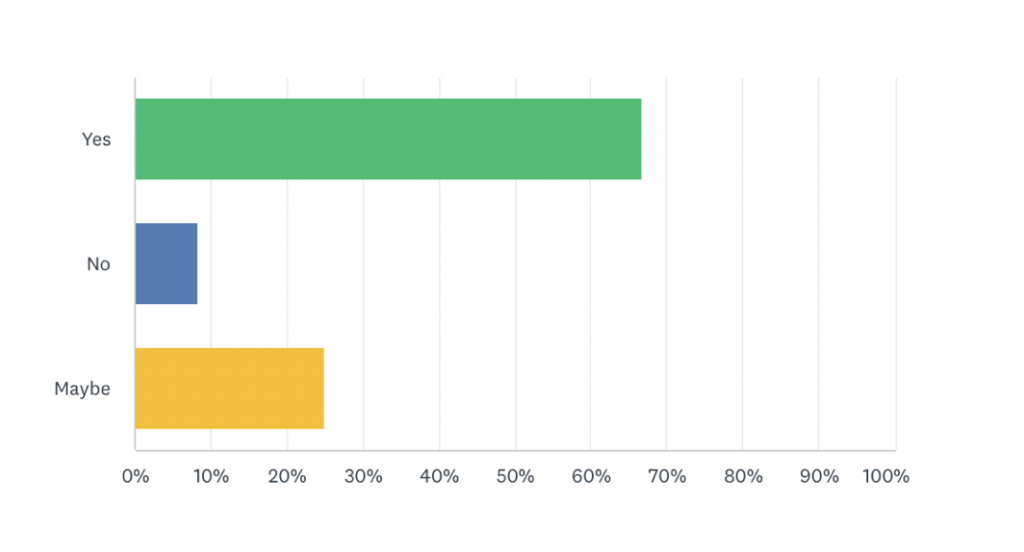

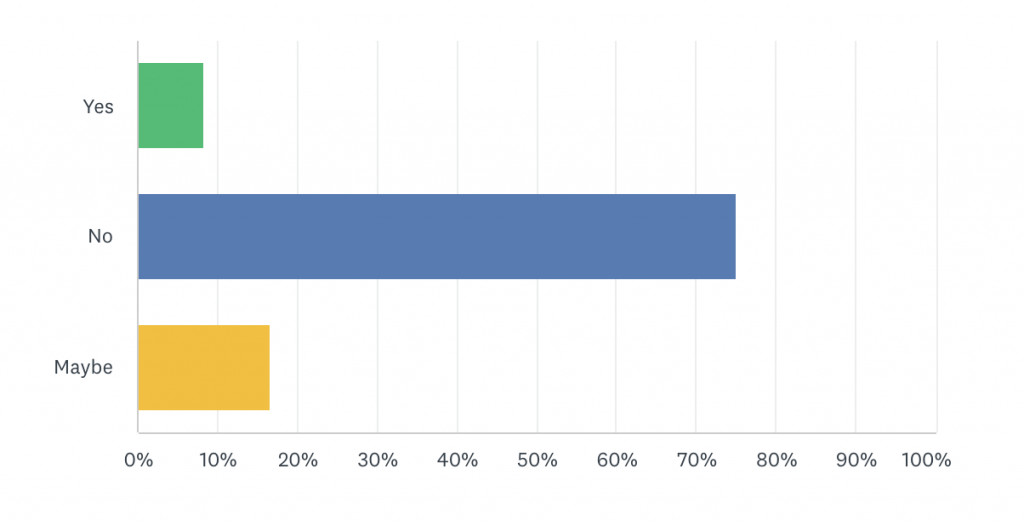

Much has been written about both the mis-selling of ESG and the exaggerated claims being made about sustainability (a.k.a. greenwashing) by the asset management industry. A survey of ESG experts within IIMI’s diverse membership revealed that 66% believed greenwashing is a major problem for the industry.

Is Greenwashing a major problem for the funds industry?

Regulators agree with this sentiment. In a Dear CEO letter penned by the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in 2021, the regulator gave several examples of ESG-focused funds whose ESG credentials it believed were somewhat questionable.

For instance, one so-called sustainable investment fund, said the FCA, had substantial exposure to high-emitting energy companies, yet did not seem to be undertaking any stewardship activities (e.g. by encouraging the companies to transition to net zero). If such behaviour is allowed to go unchecked, investor trust in ESG and sustainability funds will be eroded.

Regulators across the globe have woken up to this risk. Just as MiFID II (Markets in Financial Instruments Directive II) sought to prevent managers from selling risky products to unsuitable retail clients, the regulation is once again being updated to ensure that clients are asked about their sustainability preferences before being put into the most appropriate funds.

As well as introducing new regulations, the authorities have taken action against managers whose ESG conduct has fallen below expectations. In 2022, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) fined the asset management arm of Goldman Sachs $4 million for policy and procedural failures around its ESG research. Prior to this, BNY Mellon was struck with a $1.5 million fine from the SEC for allegedly misstating and omitting information about ESG across some of its mutual funds.[1]

With regulators putting managers’ ESG credentials under the spotlight, boutique firms should exercise caution when making claims about ESG or sustainability. Managers also need to clearly articulate their ESG or sustainability objectives to clients, so as to avoid any confusion.

- Too many cooks spoil the broth

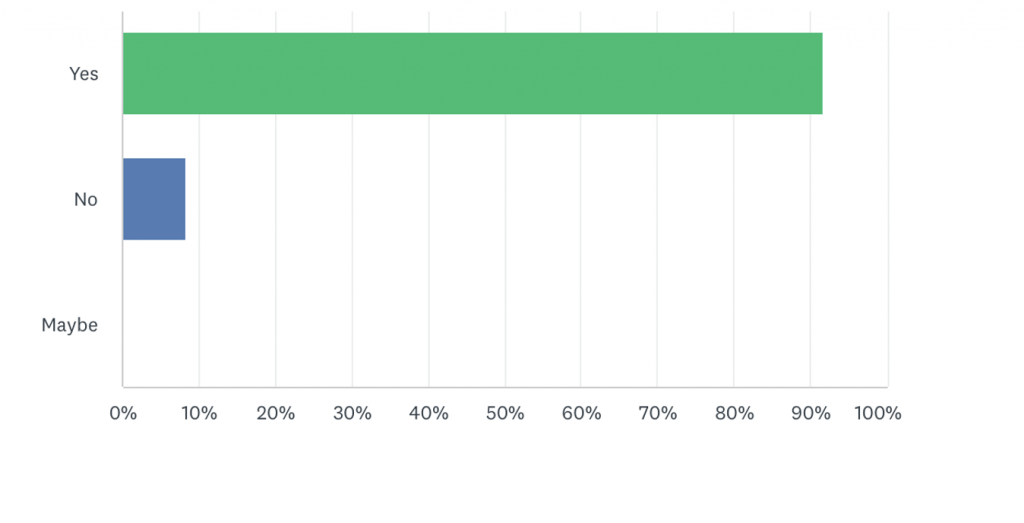

Although many regulators have made progress on ESG regulation, the lack of alignment and dialogue between the different market supervisors is a problem. Again, this deficiency is recognised by IIMI’s membership. Ninety-one percent of IIMI members complained that ESG/sustainable finance regulations are too fragmented across different jurisdictions.

Do you think that ESG/sustainable finance regulations are too disjointed across different jurisdictions?

Take what is happening in the EU and UK. Whereas the EU has imposed the SFDR (Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation), the FCA is consulting on the SDR (Sustainable Finance Disclosure Requirements). As these names imply, both sets of rules are designed to strengthen the underlying transparency of sustainable investment products and funds, but there are nuances between what the UK and EU are doing.

For example, the UK’s SDR is a labelling regime and it is not adopting some of the more restrictive provisions contained in the EU’s SFDR, such as mandated templates and the “do not harm principle”.[2] Furthermore, the EU’s SFDR allows for a so-called ‘light green’ (article 8) disclosure, whereas the FCA has a higher bar for sustainable funds. Inconsistencies of this kind between different markets’ ESG regulations risks saddling asset managers with added costs at a time when their margins are already being challenged.

It is clear the authorities need to become more consistent in terms of how they supervise ESG and sustainable investing. A failure to do so will result in confusion prevailing at investment firms and their clients. To mitigate this risk from happening, the funds industry should play a more proactive role, and engage with global regulators about the importance of having harmonised rules in place for ESG.

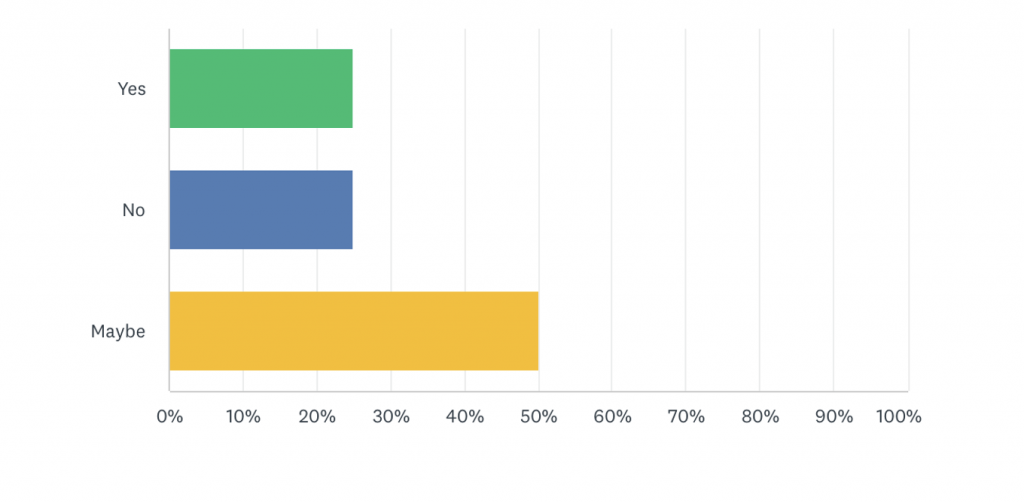

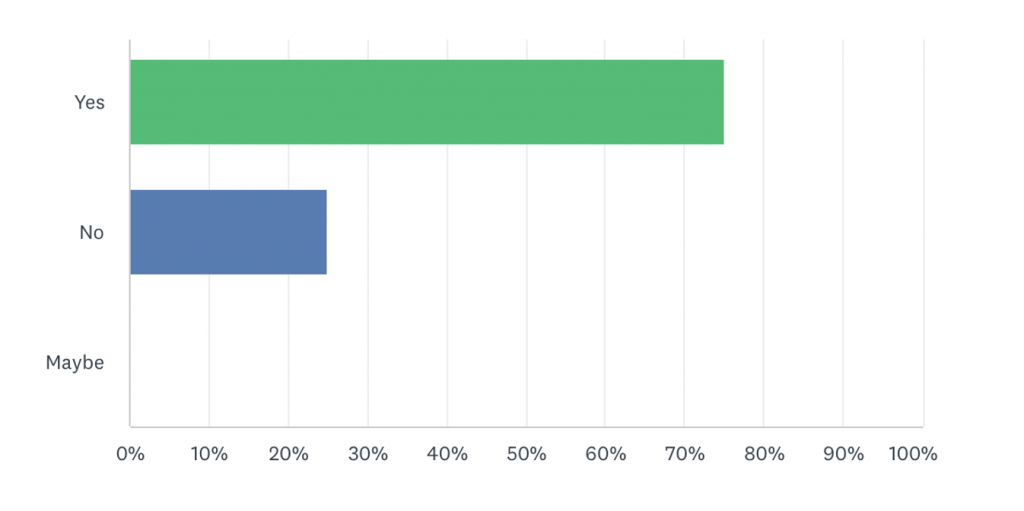

Nonetheless, IIMI members are relatively bullish that regulations will eventually facilitate inflows into sustainable investments. Twenty-five percent said regulations would definitively drive inflows, while 50% reckoned such rules would ‘maybe’ lead to more investment in sustainable assets.

Will regulations lead to substantial inflows into sustainable investments over the next few years?

- Dealing with the political fallout on ESG

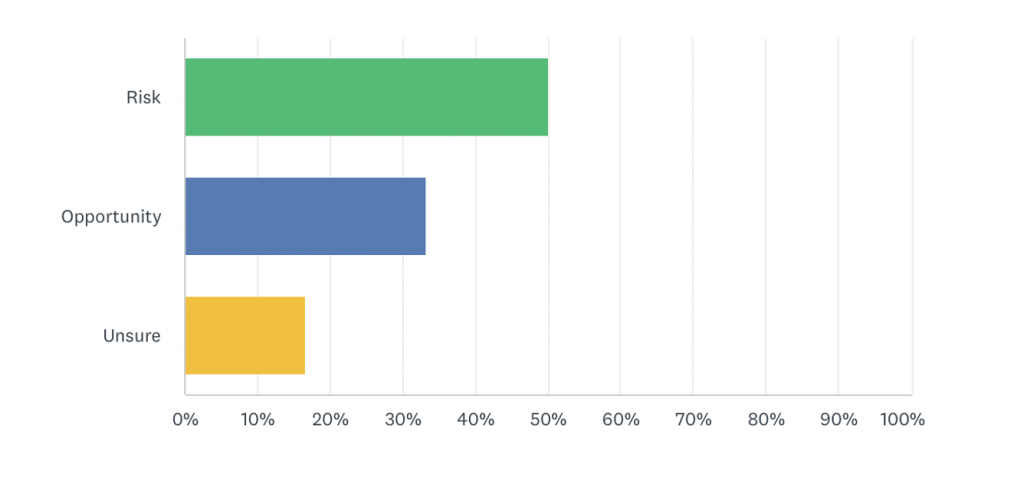

The politicisation of ESG is a risk that some asset managers are saying could impede their ability to raise funds, especially in the US. According to a survey of IIMI members, 50% described the anti-ESG movement as a risk facing their businesses.

Do you see the anti-ESG movement as being more of a risk or opportunity for your business?

So what is happening?

Hostility against ESG investing – dubbed ‘woke capitalism’ in some circles – is rising, with more than a dozen Republican-leaning US states introducing legislation aimed at limiting or even prohibiting ESG investing by public pension plans. Some of these states have even forced government pension funds to divest from money managers which take into account climate change or race issues when investing.

More recently, House Republicans voted to block Labor Department proposals allowing pension funds to consider ESG when investing and exercising shareholder rights through proxy voting.

Combating ESG hostility among policymakers is something asset managers should be thinking about, but they must approach the matter sensitively. The industry needs to tread carefully on this issue because a large chunk of its AuM is derived from US institutions in states where these rules are being enforced.

Although it is sensible for regulators to encourage investors to consider ESG when making decisions, banning or severely constraining allocators from making ESG investments altogether restricts choice, and with it the ability to obtain new sources of returns and achieve proper diversification. The funds industry needs to reach out to policymakers – especially those which may be anti-ESG – and articulate the strategic value of having ESG or sustainability-linked holdings in investment portfolios.

Elsewhere, the war in Ukraine has also created challenges for ESG investors, as fossil fuel companies have outperformed a number of other industries and sectors. Despite concerns that responsible investing would fall by the wayside as a result of the boom in fossil fuels, 75% of IIMI members said the war in Ukraine was not having an impact on their approaches to responsible investment.

Has the war in Ukraine changed your approach to responsible investment?

- Addressing new ESG paradigms

Asset managers must ensure that they stay up to speed with the various changes shaping ESG and sustainable investing.

Right now, there are growing concerns that some asset managers are not paying adequate attention to biodiversity, following a report by ShareAction, an NGO, which found just 10% of managers have a dedicated biodiversity policy in place covering all of their portfolios, while 40% of firms do not monitor whether their investee companies operate in areas of biodiversity importance.[3]

Moreover, the number of funds focusing exclusively on biodiversity is very low. According to Morningstar, there are just 14 funds collectively managing $1.6 billion, which target biodiversity as an investment theme.[4]

These findings come not long after the COP 15 Agreement pledged to reduce biodiversity losses by protecting 30% of land and sea by 2030. Post-COP 15, biodiversity risk is something which investors (and regulators) are starting to take seriously. If asset managers are to demonstrate to institutional clients that they are fully on top of ESG, they will need to develop policies outlining how they are navigating biodiversity risk, and develop strategies off the back of it.

IIMI members are themselves starting to pay closer attention to biodiversity risk, with 75% noting this is an area which they will be devoting more resources to over the course of 2023, with 44% saying this is being driven by client demand, and a further 33% by risk mitigation.

Will you be spending more time on biodiversity risk in 2023?

A blueprint for augmenting ESG in asset management

Despite the challenges facing ESG and the wider market more generally, ESG investing has proven resilient. However, it is critical that asset managers do not become complacent, otherwise appetite for ESG and sustainable funds could decline.

So what do managers need to do?

As greenwashing becomes more of a problem, asset managers will need to overhaul their communications with investors on ESG, by providing more evidence-based and granular reporting outlining how they are meeting their ESG targets and goals.

Similarly, a more robust engagement strategy is needed with regulators to counter some of the fragmentation and rising anti-ESG sentiment.

Having focused extensively on how to reduce their carbon footprints, asset managers need to start concentrating on biodiversity risk, as this is currently top of mind for policymakers, regulators, and increasingly investors.

If fund managers can achieve these goals, then the ESG market will flourish moving forward.

[1] Financial Times – November 22, 2022 – Goldman Sachs to pay $4m penalty over ESG fund claims

[2] Bovill – December 21, 2022 – SDR and SFDR – uncomfortable bedfellows

[3] Bloomberg – February 26, 2023 – Asset managers found to have blind spot around new ESG risk

[4] Morningstar – December 5, 2022 – Biodiversity – what should we expect from COP15?